Introduction.

Cherry Tree Wood is a well-loved, much used local park and small woodland. With playgrounds, a café, tennis and basketball courts, a picnic area, woodland walks and an open grassed area this small recreation ground provides a haven for people and wildlife.

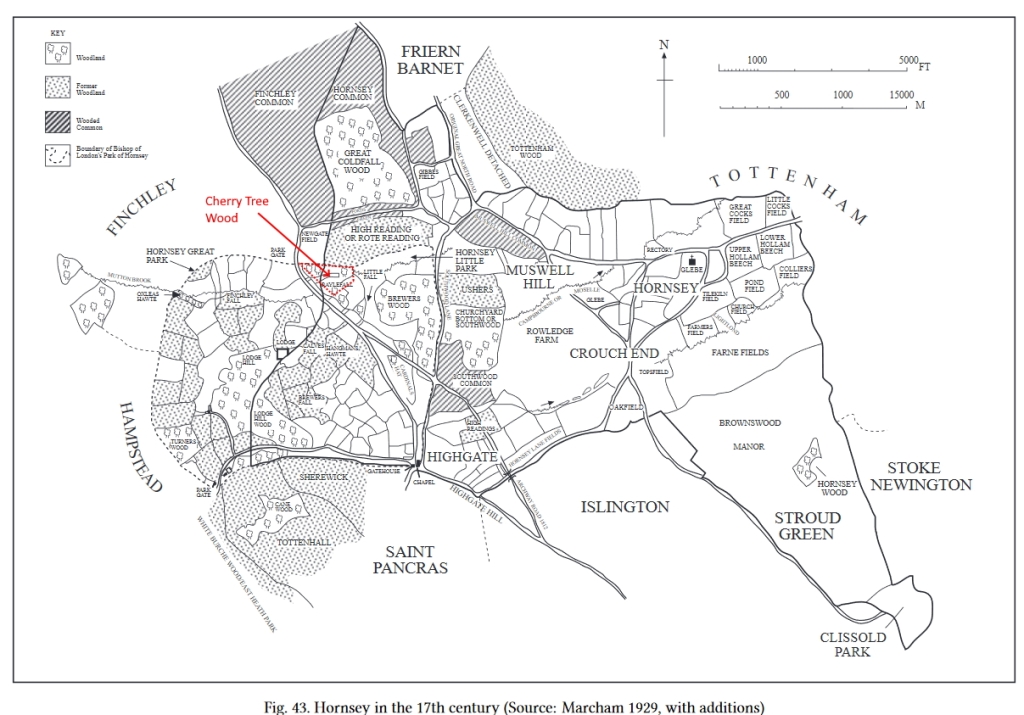

Its past is both complex and intriguing living up to one definition of history as “the past is a foreign country – they do things differently there”[1]. Cherry Tree Wood has a history that is traceable back over a thousand years and one that needs to be seen in the context of its woodland as part of a much larger, managed swathe of woodland, meadow and pasture owned by the Bishop of London including the nearby Highgate Wood, Queens Wood and Coldfall Wood. It is a history of deer parks, changing land management and the pressure for development involving railways, reservoirs and recreation.

Today Cherry Tree Wood is a 13-acre remnant of Ancient Woodland and open space in East Finchley, North London, on the boundary between the London Boroughs of Barnet and Haringey. It is owned and managed by the London Borough of Barnet as a park.

It lies in the valley of the Mutton Brook which now flows in a culvert below ground although a glimpse of this brook can be seen where it runs under the Northern line underground tracks which form the south western boundary to the Wood. Mutton Brook continues flowing west joining the Dollis Brook in Hendon then the River Brent which meets the River Thames at Brentford.

The Wood sits in a residential area with East Finchley Underground Station just across the High Road (Great North Road) from its western entrance. Within a mile is another ancient woodland: Highgate Wood, Queens Wood and Coldfall Wood which all play a part in the story of Cherry Tree Wood which now unfolds.

Boundaries to the south east and north are with back gardens and from the Summerlee Avenue entrance, the only one of the three entrances that vehicles can use, westwards it abuts the unadopted track called Brompton Grove. Geologically it lies on London Clay2 with some small superficial gravel deposits on its southern slope. A flat central grassed area is bounded to north and south by gentle, oak and hornbeam covered, valley slopes.

What is in a name?

Finchley Urban District adopted the name, Cherry Tree Wood, from Dirthouse Wood in 1913, two years before they purchased the land. The name Cherry Tree Wood had been suggested in correspondence to a local newspaper by a Mr. Binstead. Councillor Bloomfield voted against the name change as he considered it “impertinent” to change the name before the purchase of the land was complete.[2]

W e shall return to Dirthouse Wood but the name Cherry Tree Wood turns up at least one hundred years earlier and then in other references in the early 19th century. In 1813 the Hornsey Enclosure commissioners walked the boundary of the enclosure and their report notes:

“Then turning almost northwards and crossing the Turnpike Road (Great North Road) to a stone on Cherry Tree Hill standing on waste there. Then turning north eastwards through part of Cherry Tree Wood into a meadow called Quag Mead. Thence crossing Dirthouse Wood into Mr. Johnsons sheephouse Field to a stone there.”

T his suggests Cherry Tree Wood was the woodland standing on land now occupied by the Northern Line embankment then crossing a meadow (now the grassed area of Cherry Tree Wood and only then ‘crossing Dirthouse Wood.’ A lease of 1842 describes some land as: “… which said last mentioned allotment contained by admeasurement and survey one rood and twenty eight perches little more or less abut’d with on a certain wood in the said Parish of Hornsey belonging to the said reverend father and now held by the said William Earl of Mansfield as his lessee called Cherry Tree Wood east..”. This phrase is repeated in a later indenture and refers as well to the lands having been allotted as part of the Hornsey Enclosure.[3]

The name Cherry Tree Wood is therefore not as new as once thought and may be an older name that, in part at least, referred to one section of the wood and to a part that was lost in the development of the railway. However, no mention is made of Cherry Tree Wood in the development plans for the railway.

D irthouse Wood is well known as an earlier name for Cherry Tree Wood and the name by which the Wood “was known for centuries.”[4] Dirthouse Wood was the name under which the land was sold by the Ecclesiastical Commissioners to Finchley Urban District Council in 1915. The wood had long been known as Dirthouse Wood because the night soil and horse manure cleaned from London’s streets was brought as fertiliser for the hay meadows to the Dirt House, now the White Lion public house next to the station. A large field running between the White Lion pub boundary to the Bald-Faced Stag was called “Dirt House Field” in 1841.[5]

D irthouse Wood may not be a “centuries” old name. It is traceable in records during the 19th century, but another name dominates in earlier periods. The first hints are contained in documents surrendering the lease of land back to the Bishop of London from the Earl of Mansfield in 1885. A schedule in this document refers to land transferred for reasons including land for the railway in 1869 and the impact on “Rayle Fall/Dirthouse Wood.”[6]

T he name Dirthouse Wood is used by the Hornsey Enclosure Commissioners in 1813 but formal records of this date contain the older name (and one with many different spellings, “Rail Fall Wood”, “Railed Fall west”, “Rayle Fall”. It looks like local people were referring to it as Dirthouse Wood in the light of the public house and field across the road but formally it remained Rayle Fall.

A lease dated 29th June 1827 references a piece of land “..situate in the road leading from Highgate to Finchley common near the dwelling house then late of the said John Sherwood and abutting east upon that part of the Little Park called Railed Fall west on the … And land that abuts east upon … that part of Little Park called Rail Fall Wood…outbuildings and premises … called Abbots or Cherry Tree House …”[7] Page 10 of this lease contains a table which includes reference to ‘The new Inclosure by Rayle Fall Wood and meadow tenanted by John Johnson and measuring 1acre 3 roods 18perches”.[8]

I n 1647 towards the end of the English Civil War the Bishop of London lost control of his manors of Finchley and Hornsey. They were purchased by Sir John Wollaston, an Alderman of the City of London. The sale details include a lengthy list of the names of the pieces of land sold including “………Woods called Great Colefall alias Finchley Colefall, near Finchley Common …. the Little Fall against Railfall Gate … Rayle Fall, Osbornes Fall, Little Colefall, Decayed fall, Cardinalles Hatt Fall and Lyncefords Fall, being part of the Little Park of Hornsey…”[9] So apart from Coldfall Wood Sir John also enjoyed Rayle Fall and at this time there is no mention of Dirthouse Wood. The Bishop of London regained the lands after the 1660 restoration of Charles II.

T he word Fall can be traced back to one of the methods of past woodland management. A wood may be divided into a number of fells (or falls), one being cut every year according to a predetermined plan.[10] From the quote above we can see Colefall (an earlier spelling of Coldfall probably indicating the use of its felled wood to produce charcoal), Cardinalles Hat Fall and Lyncefords Fall as well as Rayle Fall. Clearly these woods were managed on a coppice cycle where once a fall, of timber, is cut down to ground level and the tree stools are left to regenerate. The coppice cycle varied and could be anything from 4 to 28 years. Oak trees within the wood were left standing and cut down for building materials. In Cherry tree Wood today, hornbeam has not been coppiced for many years and therefore you can have two or more trees growing from one stump. The name Rayle could also be indicative of the boundary of a deer park. Deer parks were bounded by a park pale, a palisade of cleft oak pales set in the ground and fastened to a rail (or “rayle”) so that the decay of one pale did not make a gap.[11] These boundaries were expensive in timber and labour. So, is there any evidence that Cherry Tree Wood was once part of a Medieval deer park?

First Records of the Wood

In the Roman period, approximately AD50–AD160 kilns produced pottery in Highgate Wood. Excavations in the 1960s–70s uncovered ten kilns and the possibility of further nearby kilns sites has been suggested.[12] The surrounding woodland – and Cherry Tree Wood is under 2 km away – along with local clay would have been exploited in this industry.[13] Charcoal used in the kilns for fuel came from oak, hornbeam and hawthorn. The woodlands were managed on a coppice system which had been in use since the iron age.[14]

The woodlands of Hornsey (which included Cherry Tree Wood) are likely to be of “primary” origin meaning continuously present since prehistoric times as it “unlikely that any extensive clearing took place on the clay before Saxon times.”[15]

In 604 AD King Ethelbert founded and built the first St Pauls Cathedral. At the same time the Diocese of London was re-established. As part of this it is likely that the King gave to the new Bishop, Mellitus, some estates in Middlesex including his Stepney estate.

In 701 AD the Bishop of London received from Bishop Tyrhtil of Hereford land in Middlesex, based on Fulham. This gift of land probably included, though as a later tenth century addition, “the solid and heavily wooded block of land to the north” comprising Hornsey and Finchley.[16]

The name Finchley was only first recoded during the thirteenth century.[17] During much of the Middle ages Finchley was treated as part of the Bishop of London Fulham Estate whilst lands in Hornsey (known also as Haringey) immediately adjoining was treated as part of the Bishops Stepney estate.[18]

The boundary between Hornsey and Finchley was not finally settled until the Enclosure of Finchley Common in 1816. The line ran through Cherry Tree Wood and when the land was bought as a recreation ground in 1915 most of the land lay within Hornsey.[19]

Neither Finchley nor Hornsey appear by name in the Domesday Book. Many stories have been sought to explain this. The most probable is that the land was assessed as being part of the Bishop of London’s Stepney (Hornsey) or Fulham (Finchley) estates. The wood in each of these estates was assessed at being able to support (through oak mast – acorns as food) 500 pigs and 1000 pigs respectively and it is likely that much of the assessment related to Hornsey and Fulham which lay in the northern part of the Middlesex where other assessments to support pigs were higher than in the south of the county.[20]

Woodland once covered most of northern Middlesex and southern Hertfordshire. Finchley Common which lay to the north of Cherry Tree Wood was known as Finchley Wood until the 17th century.[21] In 1504 it was described ‘as a common called Finchley Wood.’ Evidence for woodland to the north of London predates Domesday. The Anglo-Saxon Chronicle records a successful English counterattack made in 1016 AD against the Danes who were at that time besieging London and encamped around it on the northern side. King Edmund marched towards London from the west and “keeping to the north of the Thames all the time and coming out through the wooded slopes” surprised the Danes. It looks as if Edmund took advantage of the heavier cover all along the northern half of Middlesex.[22]

In the late 12th century William Fitzsteven, who had been at the side of Thomas Becket when he was killed in Canterbury Cathedral in 1170, wrote a biography of Becket. In this he gave a description of London which evokes the landscape in which Cherry Tree Wood sat:

“To the north lie arable fields, pastureland, and lush level meadows, with brooks flowing amid them, which turn the wheels of water mills with a happy sound. Close by is the opening of a mighty forest with well-timbered copses, lairs of wild beasts, stags and does, wild boars and bulls.”

This description of a ‘mighty forest’ may be over the top but the general gist of woodland north of London is consistent with the earlier descriptions.

The Hunting Park

T he first mention of the Bishop of London’s Hunting park is in 1227 during the reign of Henry III. A hunting park is “an enclosure which had been banked and ditched to preserve the beasts of the chase.” (Deer, wolf, wild boar, and hare) In 1241 there is the first mention of deer in Hornsey park.[23]

Ordnance Survey mapping of the nineteenth century north and west of Highgate show an unbroken hedge running from the Spaniards in a curve northwards and eastwards to the old White Lion by East Finchley Station. Most of the hedge was destroyed by the construction of Hampstead Garden Suburb but local archaeologists identified a remnant in Lyttleton Playing Fields and used dating methods to assign the hedge an approximate age of 725 years i.e. the mid-thirteenth century when the first gift of deer was recorded. In 1929 the Marcham Brothers described the boundaries of Hornsey Park.

The boundary of Cherry Tree Wood running from the High Road along Brompton Grove and then along the back of gardens in Cherry Tree Road is the boundary of the Hunting Park.

From Cherry Tree Wood (Fordington Road gate) the boundary goes across the Fortis Green reservoir and along the back of houses fronting onto Grand Avenue before cutting back along the back of properties fronting Muswell Hill Road to run along the boundary of Highgate Wood. It then followed Southwood Lane up to the Gatehouse before turning along Hampstead Lane (including shaving a part of Kenwood House land) and ending up at the Spaniards.

Sourced from Brown and Sheldon. The Roman Pottery Manufacturing site in Highgate

Great North Road

The Great North Road played an important part in the history of Cherry Tree Wood and in the history of Finchley. Finchley Wood lying north of Cherry Tree Wood, presented a significant barrier to travellers and John Norden writing in the 16th century believed that originally the route out of London made its way via Muswell Hill and Friern Barnet Lane to Whetstone bypassing the Wood. Probably in the late 13th or 14th century the change took place with the Bishop of London allowing a new road to be constructed across his hunting park, dividing it into Great and Little Park. The Great Park lay west of the Great North Road and Little Park, including Cherry Tree Wood and Highgate Wood, lay to the east.

I t is uncertain if at that time the road route passed directly northward across the Wood/common as it did by the 18th century or whether it followed East End Road through Church End along Ballard’s Lane to Whetstone.

T he Bishop of London was charging a toll in Highgate (the Gatehouse) by 1318 and a tax to cover the cost of maintaining the road was granted for the stretch from Highgate to Finchley in 1354 and the road was later maintained by the hermits of Highgate.

East End Hamlet

The hamlet of East End (as East Finchley was originally named) was centred on Market Place. It grew up near the northern boundary exit of the Bishop of London’s great park and probably developed in the 14th century when the Great North Road was built across the park heading north to Whetstone. The settlement was not right at the park gate because of the heavy local soil which drained down the hill into the hunting park – and still drains into Cherry Tree Wood today.[25]

Once the Great North Road split the hunting park in two coppice and woodland management became dominant as detailed in Leases of land by the Bishop of London. Conditions on use of the property included: “To cultivate and preserve the lands … in good order and condition and keep the same property fenced and managed according to a good and regular course of husbandry; Not to cut timber except as therein mentioned – not to grub up any of the fences but will preserve the same; Not to commit waste; To fell and cut said coppice woods in regular courses.”[26] A Woodkeeper was appointed to manage the woodlands and this role is found as late as 1906 when Frederick Locke is mentioned in connection with some illegal timber felling.[27]

Hunting, fishing and fowling took place. Leases of the royalties of fishing, fowling, hawking, and hunting in the manors of Hornsey and Finchley, Middlesex, together with the appointment of a game keeper were given at regular intervals. The rights were granted to a Thomas Rower Esq. in 1676 and 1682. Charles and Richard Bonython were granted 21 years from July 12th, 1700 and the last such lease of rights appears to be Henry Berry who was given 14 years from 27th August 1814. In 1822 Henry Berry appointed Mr John Broughton of Crouch End as his game keeper[28]

The Bishop of London’s land covering Cherry Tree Wood continued to be managed for wood and timber for the next few centuries. By an 1836 Act of Parliament the Bishops land was transferred and in future managed by the Ecclesiastical Commissioners. It was the coming of the railway in the Victorian period when greater changes began to occur.

The Railway

T he skeleton of the national railway network was ‘forged’ in the period 1830 – 1855. The northern rim of the London basin with its heights at Hampstead, Highgate and Finchley proved to be a great barrier to the early railway builders.[29] The parish of Finchley remained rural, bypassed by railways to west and east. Finchley only became “railway conscious” when the suburban revolution gained momentum in London after 1850.[30] In 1841 Finchley had a population of 3,600 and was a desirable residence for the richer classes who only journeyed to London for business purposes, perhaps once a week and they did this with their own coach and horses. Other residents were concerned with local services in and around the three nuclei of Finchley, Church End, East End and Whetstone. By 1861, while preserving its rural character, the Finchley population had risen to 4,937. A larger proportion of the population had business in London and a far greater number had to make the journey daily. The ripples of suburbanisation had reached Finchley.

Roads, although improved, were still poor. In 1861 it took the horse omnibus over an hour and a half to reach Bank from East Finchley. The Rector of Finchley, Thomas Reader White, claimed to the inquiry into the proposed railway that “a person spends more time coming from Highgate to Finchley than he would consume coming from Brighton to London by rail.”[31]

The pressure to build a railway mounted. The Parish of Finchley led the charge.[32]. The amount of woodland comprising Cherry Tree Wood was reduced with the building of the Edgware, Highgate and London Line which opened in 1867. The railway also blocked the flow of the brook and the area became boggy and was named locally as “the Quag” or “Watery Woods” but remained officially Dirt house Wood. This water proved useful to one entrepreneur who used it to grow watercress. Dirt house Wood in the 1900s still stretched as far south as Hilderidge Wood close to the foot of Highgate Hill. But with the development of Launton Road and Woodside Avenue c1910 the wood was given a new southern boundary, the one we see today.

The railway continued as an overland service until the new underground service began on Monday July 3rd 1939 at 5am. The New station, the one we use today and an extended bridge over High Road fortunately didn’t require more land from the Cherry Tree Wood.[33]

Water

F looding of parts of the central grassed area of the Wood are now common. It can be seen in both summer and winter. The East Finchley Festival in 2016 had to be cancelled for the first time in its 40-year history because of waterlogged ground. In early 2021 Kayakers attempted to use the lake. Water plays a major part in the story of the Wood.

T he slopes on both sides of the wood indicate that we are looking at a river, or stream valley. Indeed, culverted below the grass is Mutton Brook. This stream originally rose near the Everyman cinema in Muswell Hill with a subsidiary brook joining from Highgate Wood. Mutton Brook is part of the River Brent catchment so water from it flows into the Dollis Brook, then into the river Brent and eventually flows into the River Thames near Brentford.

W atercress was grown for a period. The Ham and High (20th June 1874) reported that Mr. Warren, watercress grower had written to the Metropolitan Water Board stating that his cress was dying for want of water. He asked the Board to let him have some water as if he were cut off, he would be ruined. The Metropolitan Water Board surveyor explained to the Board meeting that since the completion of the sewerage scheme on North Hill sewage had been diverted from this channel and as soon as the new portion by the farm was severed there would be less than before. Asked by a Board member if that meant the cresses had been grown in Sewage the Surveyor said “Yes.” The Board member said that the sooner they are dried up the better. Several Board members expressed regret that Mr. Warren’s prospects should be ruined but said that they could not assist him as they only diverted the sewage matter and not the surface water.

T he 1894 Ordnance Survey map shows 18 cress ‘beds’ with 3 nearby buildings. The beds fill the narrow open area that then existed. Mutton Brook is shown flowing south of the beds tight against the woodland edge.

T he Cress business met its end in the early 20th century as a result of works to construct the new Fortis Green reservoir. Between 1906-1908 the Metropolitan Water Board (which had recently taken over the New River Company and many others across London) built two covered reservoirs at Fortis Green. They were supplied from the Staines reservoirs (fed from the River Thames) some 17 miles away and conveyed in a 42-inch diameter pipe. This pipe crosses Cherry Tree Wood. Further pipe laying works were undertaken in the 1920’s and two pipes now supply the reservoir under the Wood.

“The Metropolitan Water Board when carrying their main through this ground used the lower lying area as a shoot for clay and thousands of tons were deposited on the erstwhile cress beds. The new ground was roughed level and a ‘rank vegetation’ has grown but the whole surface for feet deep is a soft clay on which it is almost impossible to walk. Moreover, the clay was dumped on the springs which form the Mutton Brook and which joins the Dollis Brook at Decoy Farm Hendon to form the River Brent. At present at the lower Finchley end is a huge swamp. It would cost many thousands of pounds before it could be made into a recreation ground.”[34]

M utton brook running above ground through the Wood is still mentioned in a 1916 newspaper report, “A ditch divides the ground, and one or two truant schoolboys are silently fishing for “tiddlers”. It is not clear when it was finally culverted.

A t some stage in its history land drains were laid across the grassed area and the diagonal pattern of them was clearly indicated by parch marks during the extremely dry summer of 2020. One issue with flooding of this area could be down to a lack of maintenance of the land drains.

Growth of the Suburb and the pressure for open space

The amount of woodland comprising Cherry Tree Wood was reduced with the building of the Edgware, Highgate and London Line which opened in 1867. The railway also blocked the flow of the brook and the area became boggy and was named locally as “the Quag” or “Watery Woods” but remained officially Dirt house Wood. This water proved useful to one entrepreneur who used it to grow watercress. Dirt house Wood in the 1900s still stretched as far south as Hilderidge Wood close to the foot of Highgate Hill. But with the development of Launton Road and Woodside Avenue c1910 the wood was given a new southern boundary, the one we see today.Finchley, at the beginning of the twentieth century, was an area of change. The population was growing, [1901: 22,126; 1911: 39,419] the pressure for services including open space was increasing. The response of the Finchley District Council in 1912 was to acquire more open spaces. The Council instructed the clerk to negotiate with the Ecclesiastical Commissioners, landowners, for the purchase of the Dirt House Wood Estate, Finchley, at a cost of £2,500. The surveyor for Finchley was asked to prepare an estimate of the cost of levelling the ground where required and provide fencing where necessary. The Hornsey Corporation were also to be approached with a view to their contributing towards the cost of the acquisition of the open space on the ground that a considerable portion of the area is within their district and would serve many persons within their area.[35]

A n Inquiry was held into an application to sanction borrowing from Public Works Loan Board of £3050 for the purchase. The Wood comprised 13 ½ acres of land; 10 in Hornsey Parish and 3 ½ in Finchley Parish. Hornsey Parish had refused to give anything so the cost to Finchley would be £234 10s per acre.[36]

The inquiry was not straightforward. There was strong opposition to the loan “a more unsuitable piece of land for a recreation ground cannot easily be found near Finchley.” It is “virtually a clay heap”.[37] The Council pressed ahead and in the same month as the Inquiry was taking place October 1913 the Town Planning Committee made recommendations for development of the Wood including:

I) widening the entrance around the railway bridge with a view to this being the main entrance.

II) that a kissing gate be fixed as an entrance from Park Hall Road.

III) a plan was to be prepared showing the laying out of four cricket pitches and the rest of the land in the open for tennis courts.

IV) a 12-foot path running round the ground.[38]

T he acquisition ground slowly through the bureaucratic processes. In July 1914 Middlesex County Council agreed to contribute £780 7s 6d towards the cost of acquiring Cherry Tree Wood. The County Council noted that the Wood was easily accessible being close to East Finchley Station and to the Great North Road “along which the Middlesex County Council trams run at frequent intervals”.[39] On the reasons to support it the Council observed that, “it is in proximity to a large residential population of the middle and artisan classes, whose wants it is intended to serve,” several schools were in the vicinity, the nearest public space was more than a mile distant, and the combination of woodland and grassland is unusual and makes the area additionally attractive. The price was about £240 per acre and no other vacant land in this portion of Finchley was lower than £500 per acre. Part of the reason for the low price was put down to the “New River pipes from Staines Reservoirs running through part of the ground” which the Metropolitan Water Board had a right to access though it was acknowledged that this did not affect the use of the ground as open space.[40]

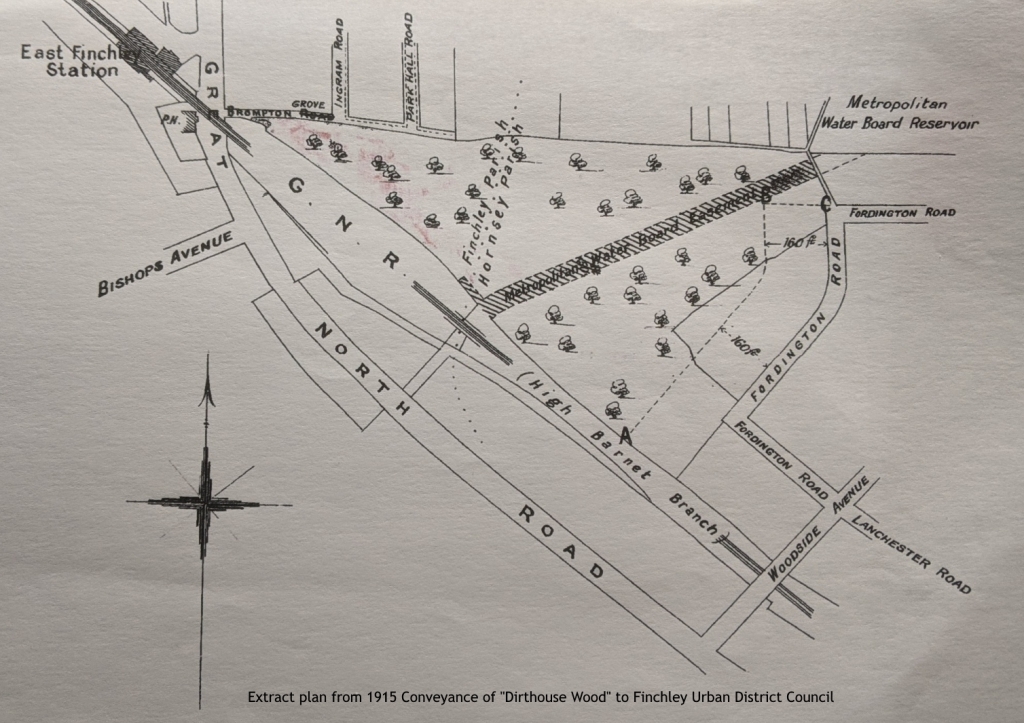

T he outbreak of the First World War probably slowed down the purchase of the site but by May 1915 the Council was able to fix a date for completion of the sale as 11th June.[41] Some further short delay took place as the Conveyance is dated 29th July 1915 between the ‘Ecclesiastical Commissioners for England and The Finchley Urban District Council. It conveys the ‘hereditaments known as Dirthouse Wood in the Parishes of Hornsey and Finchley in the County of Middlesex’ The sum of £3050 was paid to the Ecclesiastical Commissioners by Finchley Urban District Council for the land.

The Conveyance contains a plan (scale 1:2500) showing the land to be conveyed and includes:

I) The Finchley and Hornsey parish boundary

II) A Metropolitan Water Board easement (50 feet wide) running north east-south west from the reservoir across the wood towards the railway.

III) A 160ft strip of building land retained by the Commissioners for building houses on Fordington Road.

IV) A field boundary line cutting across the eastern part of the wood at the back of the strip of building land.

V) No access points are indicated on this plan.

The conveyance notes that the Council were purchasing the land ‘for the purpose of a public recreation ground.’ It further notes some ‘rights and liberties granted by the Commissioners to the New River Company under an indenture dated the first day of May One thousand nine hundred and two.’

A n obligation is placed on the Council to construct an ‘Oak cleft fence six feet in height’ between the points marked A, B and C on that plan – which is the strip of building land set aside for the Fordington Road development – and to maintain this in good repair. The Council also had to erect a gate at point C (Fordington Road entrance) to provide access to the recreation ground. The Commissioners agreed to fund half the cost of the fence.

T he Wood was formally opened to the public on Monday 2nd August 1915 but “without ceremony.”[42] A piece in the Hendon and Finchley Times under the heading “A new pleasure resort” considered that although the “wood is not large, it is a pleasant enough piece of woodland scenery, and has not that worn out appearance which many older stretches of public ground possess.”[43]

B y 1916 the view of the wood as a ‘pleasant enough piece of woodland scenery’ was under attack. An Ironic and savage article on the state of Dirt House Wood “Impressions of a Finchley pleasure Ground” appeared in the Hendon and Finchley Times on Friday 1st September. It starts with an extract from the poem Kubla Khan by Samual Coleridge

“A savage place! As holy and enchanted

As e’er beneath a waning moon was haunted

By women wailing for her demon lover”

This opening paragraph sets the tone. “No birds sing there, nor does the rabbit peep timidly out from the bracken, nor do the tram companies advertise it as the “home of the squirrel” – it is a savage and almost deserted spot, resembling a piece of waste ground in Gehenna.”[44]

It continues in similar vein noting that when you enter you see a vast number of carefully shaped stones lying around which you might think “belong to the Druid age”. Looking closer you see that they are Finchley Urban District kerb blocks that give “the appearance of a builders yard.”

The author then evokes scenes in Macbeth where the witches leap and reel demonically at midnight which Shakespeare designates a “blasted heath” but he notes that there are people around the place. “A ditch divides the ground, and one or two truant schoolboys are silently fishing for tiddlers.” A forlorn little girl is examining the bushes for blackberries.

A t night it is said that “strange screams haunt the place, and an agitation is afoot because the goings on are not respectable.”. The author notes that it is just over 12 months since the Council declared the Wood open having purchased it for £3000 but he asks might another £100 have been spared to make the place look less like the dumping ground it really was.

The author notes that it is just over 12 months since the Council declared the Wood open having purchased it for £3000 but he asks might another £100 have been spared to make the place look less like the dumping ground it really was.

H e concludes “The writer, on his visit, turned his back on the spot for ever in a cloud of unlifting gloom. He stumbled heavily as he made for the gate – he had caught his foot in a broken beer bottle.”

T here remains a fair bit of dumping to this day and bottles are certainly not a rarity but clearly investment in the Wood during this war period didn’t appear to be a priority for the Council. Local people continued to push for improvements.

The pressure for improvements and use as a recreation ground

T he author notes that it is just over 12 months since the Council declared the Wood open having purchased it for £3000 but he asks might another £100 have been spared to make the place look less like the dumping ground it really was.Residents continued to complain about the lack of investment in the Wood. The East Finchley Ratepayers deputation to Finchley Council about the Wood complained about the lack of investment in this “beautiful piece of old rural Finchley”. They claimed it was effectively closed except for 3 months of the year due to wet conditions underfoot. They complained that the purchase of the Wood “…was like spending money on buying a house and then failing to spend money on a key to open it.”

T he East Finchley Ratepayers suggested several improvements including “the planting of fruit trees and provision of seats the laying out of cricket and football pitches, tennis and bowling greens” They also proposed an ornamental lake, bandstand, tea gardens and a lodge.[45] Councillor Cope noted that to plant fruit trees in a public place,” is asking for trouble.”

The cricket pitch was provided but not much else. A Hendon & Finchley Times report of Friday 27 January 1922 notes that a proposal to lay out tennis courts was discussed, and the Surveyor was asked to obtain estimates. East Finchley Tradesman’s Cricket Club had been allocated the cricket pitch on Thursdays at 5 guineas for the season and the East Finchley Cricket Club and Holy Trinity Cricket Club jointly for use on alternate Saturdays at 3 Guineas per club.

I n 1925, as part of a scheme to help combat unemployment the Council discussed the provision of three tennis courts. This was part of a wider provision of works for the unemployed across Finchley. This proposal was hotly contested. Some concerns were expressed by Councillors that the works across the District would be too expensive to maintain. Others supported the provision of work for the unemployed, 242 men being on the register, but it was anticipated that over double that number were without work. The specific discussion on tennis courts in Cherry Tree wood found Councillor Bowen arguing for the claims of that congested part of the neighbourhood for improvement whilst Councillor Lawrence considered it a pity to destroy the “sylvan beauty of this child’s paradise” by placing tennis courts there.[46] The proposals were agreed.

F urther improvements took place in the 1920s. The entrance to the wood from the High Road was improved and further water main works were to be undertaken.[47] The water main works through the wood finally took place in 1929 and seem to have caught the Council by surprise. A newspaper article in August that year reports the Council only just finding out that works are to “proceed immediately” and the contractor was “on the edge of Cherry Tree Wood.” Councillors agreed to write to the Metropolitan Water Board taking “strong exception to the interference with public enjoyment during the summer months which would be caused by the action now contemplated “and hoped they would reconsider their decision”.[48] The Water Board didn’t, and the works proceeded.

P ressure was also growing to locate an electricity substation in the Wood. By the mid-1920s demand for electricity increased with new housing in the Hampstead Garden Suburb. Councillor Bennett (Chairman of the Electricity Committee) said that another substation was needed at East Finchley. The design of the building was discussed with final agreement on it being “camouflaged” by building a verandah around three sides of it. The building formed part of the Finchley Corporations electrical distribution from its works in Squires Lane. Here 6600 (AC) was converted to 250 volts for domestic use. Sister sub stations still exist in Regents Park Road and Victoria Park, both in Finchley Central, and all three had distinct air vents in the roof. Messrs. J Harrison and Co won the tender to build the pavilion with a bid of £210 10s.[49] By 1955 Finchley Corporation had handed over the responsibility for the generation to the Eastern Electricity Board. In 2020 the now redundant building was demolished although a smaller modern substation still stands nearby.

A ntagonism between Finchley and Hornsey over the wood, possibly resulting from Hornsey not contributing to the purchase of the land, can be detected in 1926. The Muswell Hill Traders Association sought permission from Finchley Urban District Council to use Cherry Tree Wood for their sports day. One Councillor objected to any park being closed on a Saturday. Councillor Leslie said, “These are not Finchley people; they are a Muswell Hill crowd” The request was rejected. [50]

I n 1929 East Finchley was being described by Mr. James, President of the East Finchley Residents Association at one of their meetings as the “Cinderella of Finchley” and noting that Cherry Tree Wood did not receive as much attention as the Victoria Recreation Ground. This was in the context of a discussion about improving entrances to the Wood. One suggestion was to create a new entrance direct from the main road (present day Cherry Tree Hill) on land owned by the water board and to improve the entrance off Brompton Grove.[51]

D uring the 1930s a range of “improvements” were occurring. In 1930 a new 18 hole putting green had opened at Cherry Tree Wood. A round cost 4d which included use of a putter. “The green is very pleasantly situated, trees and shrubs surrounding it. No doubt large numbers of the public will attend such an attractive place in large numbers.”[52] Later that year it was reported that the caretaker’s bungalow had been completed at a cost of £669 7s 8d.[53] The bungalow was eventually sold and the land lost to Cherry Tree Wood in the 1990’s.

T he Wood has a long history of commemoration with many benches and trees being dedicated to the memory of others. Historic events were also noted and a Coronation Oak celebrating the new King George VI was planted in in 1937 not far from the current café[54]

Cherry Tree Wood at war

T he second world war led to some new activities. Even before the outbreak of war Anderson air-raid shelters were on display in Cherry Tree Wood and Avenue House Grounds.[55] Throughout its history as a park debate has raged about locking the Wood at night or leaving it open. In 1941 there was pressure on the Council to leave the Wood unlocked to allow fire watchers and others access to extinguish any incendiary bombs that might fall. This move was rejected, and the Wood remained closed, along with other open spaces, on the basis that the existing opening arrangements were adequate.[56] Also, in 1941, the Home Guard was directed to dig a few slit trenches in Cherry Tree Wood and was making application to the Council for permission to carry out the works. Permission was granted subject to the actual position of the trenches being approved by the Borough Surveyor.[57] If anyone has more information on whether these trenches were dug, and their location please let us know.

P art of the war effort aimed to boost the supply of steel for aircraft, tanks and other military equipment. A component of steel production was iron and significant efforts were made in removing iron railings and gates around the country. In October 1941 Finchley Urban District Council were ordered, by the Ministry of Supply, to carry out a survey of “unnecessary railings” around open spaces. A schedule was produced which showed Cherry Tree Wood to have railings that were “unnecessary”. The survey reported back in February 1942 and recommended that all the iron fencing and gates at Cherry Tree Wood be released but that the question of liability to maintain a fence along the backs of houses in Cherry Tree Road be investigated by the Town Clerk, and that where gates were removed on the northern boundary, posts with reflecting studs be erected; that the end of the pavement in Summerlee Avenue also be safeguarded and that ‘No parking’ notices be placed as necessary where gates are removed.[58] The Council could claim 30s a ton for removal including cartage etc. plus 25s a ton compensation for the metal removed, and reasonable costs of making good were chargeable.

W hat happened to the iron railings and gates from Cherry Tree Wood? It is a good question but difficult to answer. Research by the London Gardens Trust notes that around the country the removal of the iron is recounted by hundreds of eyewitnesses, but there are no similar reports of the lorries arriving at steel works with large quantities of railings and gates to be loaded into the blast furnaces. So, what did happen? One school of thought says the iron collected was unsuitable and could not be used. This seems unlikely as recycled iron is a key component in the steel industry. Another more likely explanation is that far more iron was collected – over one million tons by September 1944 – than was needed or could be processed.

A fter the war, even when raw materials were still in short supply, the widely held view is that the government did not want to reveal that the sacrifice of so much highly valued ironwork had been in vain, and so it was quietly disposed of, or even buried in landfill or at sea. This is the view of John Farr, author of an article in Picture Postcard Monthly, (‘Who Stole our Gates”, PPM No 371, March 2010). In it he says that only 26% of the iron work collected was used for munitions and by 1944 much of it was rusting in council depots or railway sidings, with some filtering through to the post-war metal industry. Yet the public was never told this.[59]

Post war

A fter the war the Wood continued to provide a range of recreation for local people. The kiosk catering rights were let on an annual renewable contract and in the early 1960s a shelter was built over the paved area.[60] The football pitch was let to clubs. Through the 1950s it often alternated between the Borough Education Officer and the Finchley All Blacks Football Club with the Borough getting preferential rates of £6 a season compared to £9 for the All Blacks.

East Finchley Community Festival

E arly in the 1970s the first annual East Finchley Community Festival was held in the Wood. It has been operating for nearly 50 years and merits its own history. It prides itself on being an inclusive festival with a welcome given to ALL within our community, free at the point of entry. It is a community festival – not a commercial festival. The Festival was banned on political grounds by Barnet Council in 1989. The Court of Appeal in July 1990 held that the Council had exceeded its powers by refusing to give the Festival grant aid and permission to stage its event on council owned open space. The only other times it has not run have been in 2016 due to flooding of the central area and regretfully in 2020 and 2021 during the COVID 19 pandemic which saw lockdowns and major disruption across the globe.

The Friends of Cherry Tree Wood

The Friends of Cherry Tree Wood registered as a charity in 1996 and have these charitable objectives:

T o promote high standards of planning and architecture. [2] to educate the public in the geography, history, natural history and architecture. [3] to secure the preservation, protection, development and improvement of features of historic or public interest in the area of benefit – which is Cherry Tree Wood and the surrounding area.

F rom 1999 the Friends produced a regular newsletter for the next 10 years which gives a good flavour of activity and works undertaken during this period. In 1999 the Hendon to Highgate section of the Capital Ring, a 75 mile round London Walking route, was opened in Cherry Tree wood by the Mayors of Barnet and Haringey and Deputy Chairman of the London Walking Forum.[61]

It was reported that the Woods were to be left open at night and that the savings from this would be used to employ a park keeper. There was concern about the future of the pavilion, built originally as an Electricity Step down station with agreement that the structure should be made safe but not extended. The kiosk café was to be improved by restoring the wet weather shelter which had been dismantled some years ago. A Woodland Management group met on 10th May 1999 to begin drafting a strategy for Cherry Tree Wood with their first site meeting on 19th July. Various dates for practical conservation work were arranged. A new landscaped quiet area, formerly the old putting green, was agreed to be laid out with picnic benches, low hedge etc. On the 4th July a litter pick attracted 12 volunteers who collected 15 bags of litter. At the end of August new park Keeper Chris Ward started work. In winter 36 young oaks were planted in an unmarked spot – so called ‘discrete planting’. Several Turkey Oaks were dug up and some sycamore cut back. By Spring 2000 it was noted that no new litter picks were needed as the park Keeper is “doing such an excellent job”. The pavilion remained derelict and plans for development had still not gone out to tender.

T he Wood has protections against development. It is designated as Metropolitan Open Land and as a site of local interest for nature conservation. In 1997 a detailed report on its ecological value was produced by the London Ecology Unit and over the next decade in fits and starts some woodland management was undertaken. The departure of the Countryside Management Service due to ‘cutbacks’ put paid to concerted woodland management work around 2005.

T he Friends have battled over many years to protect the Wood and seek to maintain it, but lack of investment has led it to look down at heal to many eyes in recent years. A reinvigorated Friends group is trying to tackle some of the many issues that require attention. A successful £20,000 bid for funds to carry out small scale works, such as a new noticeboard, improving flowers beds and bulb planting are being implemented. A gardening group has been formed and a group is beginning to look at the future of the playground.

Cherry Tree Wood – What next?

O ur local wood has over 1000 years of traceable history. It was documented for the first time in Mediaeval Manorial history as part of the Bishop of London’s deer park and estate land holding in Middlesex. It has been transformed by major transport changes. First with the new route for the Great North Road dividing the deer park in two (Little Park, including Cherry Tree Wood and Great Park) during the fourteenth century and then in the 19th century cut through by the railway which began to unleash the suburbanisation of this very rural area. Coppice woodland management probably with some meadow and pasture dominated its land use with cress and osier beds appearing in Victorian times. The early 20th century saw major water infrastructure works connected with building Fortis Green Reservoir reduce the extent of woodland further and this was exacerbated with the sale of the Wood to Finchley urban District Council in 1915 with a chunk of land being felled and excluded from the sale for the construction of houses in Fordington Road.

I n its life during the twentieth century as a park/recreation ground/wood it has seen facilities provided – cricket pitch, football pitch, putting green and electricity step down station/pavilion which have now all gone. Political controversy erupted in 1990 with the decision of Barnet Council to ban the annual Community Festival held in the Wood being overturned by the Court of Appeal. In the twenty first century the Tennis and basketball courts (March 2021) are being refurbished, the playgrounds need attention, the kiosk will hopefully be let again soon having languished in a longer lock down than the rest of us have had with COVID 19. The toilets, gates and fences along with parts of the wooded areas need a lot of love, care and attention. Drainage problems on the grassed area are becoming ever more frequent and need work. On the upside a new community orchard planted and cared for by the Friends has survived its first year and the new Monkey Puzzle Forest School in the wood is blooming.

C ovid 19 has helped a lot of people to discover the delights of our wood for both physical and mental health benefits. Cherry Tree Wood is a wonderful resource for our community. It needs our community to continue to fight for it. You can help us do that by joining the Friends of Cherry Tree Wood. We don’t charge. Just email us at [email protected] and you become a big part of ensuring another 1000 years of history for Cherry Tree Wood.

Bibliography

Borough of Finchley – Programme of Coronation Celebrations. (1953). Borough of Finchley.

Brown A.E. & Sheldon H. L. (2018) The Roman Pottery Manufacturing Site in Highgate Wood Excavations 1966 -1978 Archaeopress Roman Archaeology 43

Bygone Finchley – an annotated catalogue of pictures, maps, books, and photographs. (1947). London: Borough of Finchley.

Collins, A.B. (1958). Finchley vestry minutes, 1768-1840. London: Finchley Public Libraries Committee.

Denford, S. (2008). Hornsey past : Crouch End, Muswell Hill, Hornsey. Historical Pub.

Finchley Official Guide 1940 – 41. (1940). Borough of Finchley.

Gillies, S., Taylor, P. and Barnet Libraries, Arts And Museums (1992). Finchley and Friern Barnet : a pictorial history. Chichester: Phillimore.

Godfrey, Al. (1985). Muswell Hill 1894 -London Sheet 11.

Gurney, T. and Phillimore, W. (1915). Middlesex Parish Registers. Marriages. London: Phillimore.

Hacker, M. (2017) The history and archaeology of Queens Wood.

Heathfield, J. (2001). Finchley and Whetstone past: with Totteridge and Friern Barnet. London: Historical Publications.

Know your Finchley – Official handbook of the Borough of Finchley. (1955). London: Borough of Finchley.

Latimer, Dr.A. (n.d.). The Illustrated story of Finchley. London: Bradmores.

Lawrence, G.R.P. (1964). Village into borough. Finchley Public Libraries.

Official Souvenir on granting of a Charter of Incorporation. (1933). London: Finchley Urban District Council.

Royal Silver Jubilee Celebrations 1935. (1935). Finchley Borough Council.

Schwitzer, J. and Gay, K. (1995). Highgate and Muswell Hill. Stroud: Chalford.

Taylor, P. ed., (1989). A Place in Time. The London Borough of Barnet up to c.1500. First ed. London: Hendon and District Archaeological Society.

Taylor, P. (2002). Barnet and Hadley past. London: Historical Publications.

Tiller, K. (2020). English local history : an introduction. Woodbridge The Boydell Press.

Whitehead J. (1995). The growth of Muswell Hill. London

William Mcbeath Marcham, Marcham, F. and Hornsey Manor, England (1929). Court rolls of the bishop of London’s Manor of Hornsey, 1603-1701,. London, Grafton.

Wilmot, G. (1973). The Railway in Finchley. Barnet Council.

[1] L. P. Hartley The Go between

[2] Hendon & Finchley Times – Friday 26 September 1913

[3] LMA DL/D/L/223/MS12397 Cherry Tree Wood is also cited in a lease of 1837 DL/D/L/225/MS12399

[4] Marcham WM and Marcham F. (eds) 1929 p14

[5] Lawrence, G. R. P. Fig 5 pages 30 – 39

[6] DL/D/L/225/MS12399 Third Schedule

[7] DL/D/L/225/MS12399

[8] https://lochista.com/understanding-acres-perches/ Accessed 24th March 2021 Roods & perches. These are subdivisions of an acre. There are four roods in an acre, and in turn a rood contains 40 perches. As a rood is a quarter of an acre, it contains 1.012 square metres – about the size of two tennis courts. Each of the 40 perches in a rood thus consists of just over 25 square metres – the size of one of the net-side playing areas of the tennis court.

[9] Marcham WM and Marcham F. (eds) 1929 (p xix-xxi)

[10] Rackham, O. Ancient Wood land 1980 p137

[11] Rackham, O. p.191

[12] Brown A.E. & Sheldon H. L. (2018)

[13] Silvertown

[14] Rackham

[15] Silvertown

[16] Taylor, P. The history of St. Pauls (forthcoming?)

[17] Victoria County History. Finchley introduction; in a History of the County of Middlesex: Volume 6. 1980

[18] Sullivan, D. (1994) The Westminster Corridor. P 18

[19] Victoria County History. Finchley introduction; in a History of the County of Middlesex: Volume 6. 1980.

[20] Sullivan, D. (1994) p. 34

href=”#_ftnref21″>[21] VCH p. Finchley intro p 55

[22] Sullivan, D. (1994) p. 34

[23] Stokes, M. 1984 p.?

[24] Victoria County History. 1980. Hornsey with Highgate

[25] Taylor, P. (1989) Old Ordnance Survey Maps East Finchley 1894. The Godfrey edition.

[26] DL/D/L/225/MS12399 p.29

[27] Hendon and Finchley Times 7th December 1906. The felling of these trees was in connection with the new pipework being installed underground to serve the newly constructed Fortis Green reservoir

[28] DL/D/L/220/MS12394DL/D/L/223/MS12397

[29] Wilmot, G. The Railway in Finchley. 1973

[30] ibid. p4

[31] ibid. P 7

[32] The parish was the Local authority of its day for the area.

[33]Hendon & Finchley Times – Friday 30 June 1939

[34] Hendon and Finchley Times 18th October 1912

[35] Hendon & Finchley Times, London, Friday 21 June 1912, England

[36] Hendon and Finchley Times 18th October 1912 It was not until 1932 that boundary Changes were agreed between the Borough of Hornsey and Finchley Urban District Council so that in future the whole of Cherry Tree Wood would lie in Finchley. Prior to that it was divided between the two Councils with most of the land in Hornsey.

[37] Hendon & Finchley Times – Friday 31 October 1913

[38] Barnet and Finchley Press p.5 31/10/1913

[39] Hendon & Finchley Times – Friday 31 July 1914

[40] ibid

[41] Finchley Urban District Council Minutes 1915-16. Town Planning Committee 11th May 1915. p. 86 item (d) Cherry Tree Wood

[42] Finchley Urban District Council Minute 26/7/1915 p326-327. (b)

[43] Hendon and Finchley Times 6th August 1915

[44] Gehenna abode of the damned in the afterlife in Jewish and Christian theology. https://www.britannica.com/topic/Gehenna Accessed 15th March 2021.

[45] Hendon & Finchley Times – Friday 31 January 1919

[46] Hendon & Finchley Times – Friday 30 January 1925

[47] Hendon & Finchley Times – Friday 28 May 1926

[48] Hendon & Finchley Times – Friday 09 August 1929

[49] Hendon & Finchley Times – Friday 08 April 1927

[50] Friday 04 June 1926 Hendon and Finchley Times.

[51]Hendon & Finchley Times – Friday 18 October 1929

[52] Hendon & Finchley Times – Friday 06 June 1930

[53] Hendon & Finchley Times – Friday 26 December 1930

[54] Hendon & Finchley Times – Friday 26 March 1937 The George IV oak is located near to the Tea kiosk. For many years it had a plaque explaining when and why it was planted. The plaque has disappeared, and thought is being given to replacing it. The Oak in the triangle of land opposite the kiosk was planted in 1990 to commemorate Robin Chapman one of the founders of the Friends of Cherry Tree Wood.

[55] Hendon & Finchley Times – Friday 30 June 1939

[56] 6th May 1941 Parks and Opens spaces minutes. Finchley Urban District Council.

[57] FUDC Council Minutes 27/09/41 Min 1710 Defence Works

[58] Report of the Sub-Committee re: Inspection of Iron Railings around open spaces in the Borough 14th February 1942. Min 438.

[59] See https://www.londongardenstrust.org/features/railings3.htm accessed 3rd January 2021

[60] M1197 p489 Catering Contracts

[61] The Capital Ring is a 98 mile circular walk around London utilising many green spaces such as Cherry Tree Wood, Highgate and Queens Wood, Parkland Walk, Finsbury Park etc.